The Governing Mandate

Asset Retirement Obligations and Environmental Remediation Obligations appear as singular Environmental Obligation line items on the balance sheet. In practice, the activities required to identify, govern, measure, and ultimately derecognize Environmental Obligations span multiple functions, geographies, and time horizons. This creates a fundamental governance requirement: Environmental Obligations demand shared input, but they require unified ownership.

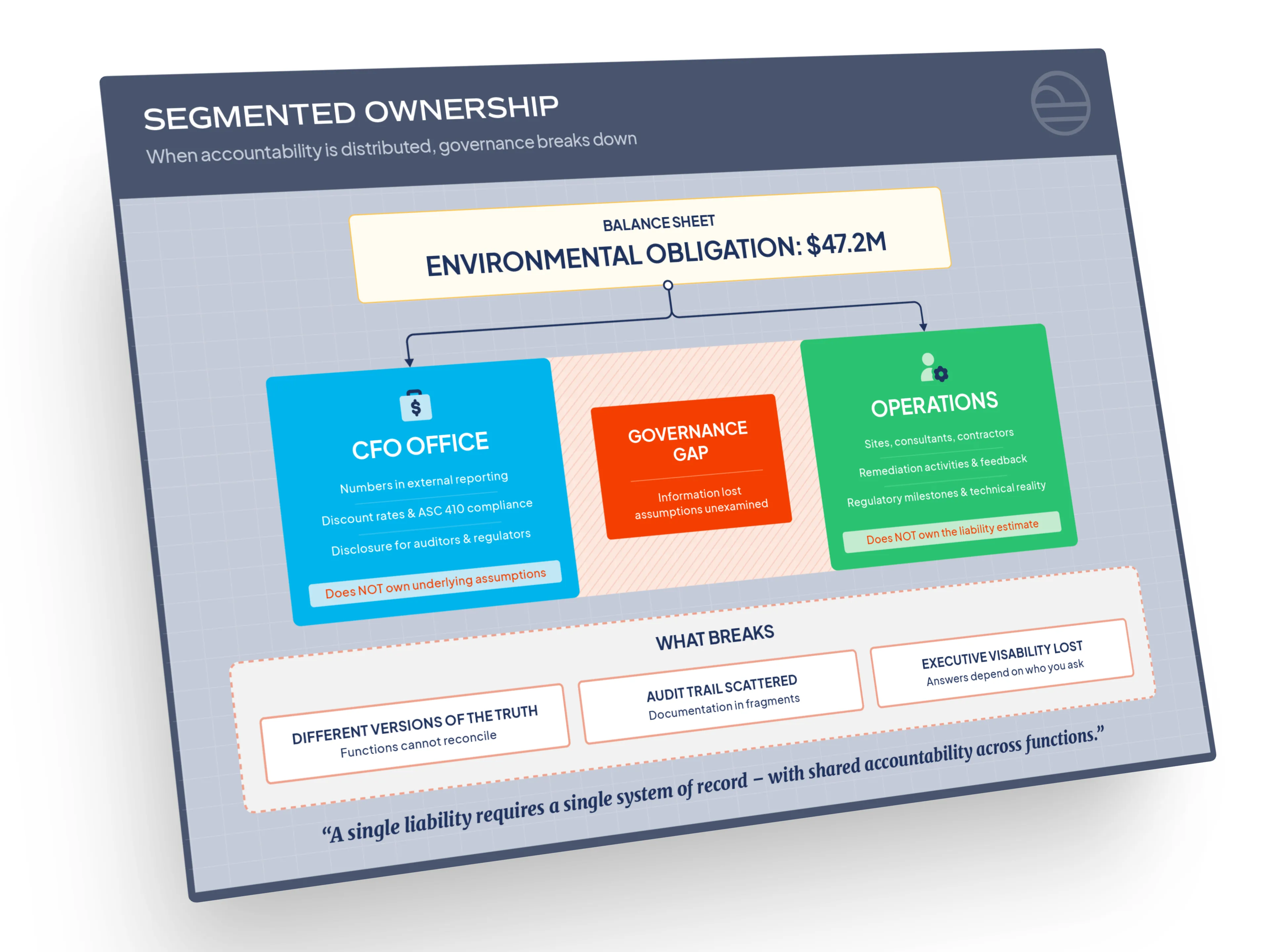

That unified ownership rarely exists. Accountability is distributed across accounting, operations, legal, and external service providers, with each group responsible for a discrete portion of the Environmental Obligation lifecycle. No single function owns the complete picture as a system of record. Responsibility is shared, but control is not. The result is segmented ownership.

This fragmentation is not a failure of intent or organizational design. It reflects the inherent complexity of Environmental Obligations. Technical accounting expertise is required to apply ASC 410 and IAS 37 and support financial reporting and audit readiness. Operational teams provide site-level context and factual inputs that inform obligation status. Legal functions interpret environmental laws, permits, and contractual commitments. Auditors evaluate the integrity of the resulting disclosures. Executives rely on all of these inputs to govern material balance-sheet exposure.

Environmental Obligations require cross-functional participation. They also require centralized governance.

The Structural Breakdown

No single function possesses all of the competencies required to govern Environmental Obligations end-to-end. Environmental Obligations do not conform to organizational charts. Traditional governance models do. That mismatch is where control breaks down.

Ownership fragments along predictable lines. Accounting owns the Environmental Obligation liability recorded on the balance sheet and the associated accounting assumptions. Operations owns site-level information and obligation-related facts that inform status and timing. Legal and real estate functions track obligations tied to property, transactions, and regulatory commitments. External consultants often document significant portions of the underlying work. Each group maintains its own tools, data structures, and timelines.

These systems are not integrated. Accounting maintains models and summaries designed for financial reporting. Operational information resides in project files, spreadsheets, and point solutions not designed for financial governance. Legal documentation exists separately. Shadow systems emerge to bridge gaps manually. As a result, the same Environmental Obligation is represented differently depending on which function is asked.

Transparency fails at the handoffs. Governance frameworks assume clear information flow between functions. In practice, assumptions go unexamined, documentation is incomplete, and historical decisions are difficult to reconstruct. The organization operates with multiple versions of the truth and no authoritative system of record.

Segmented ownership persists because it is tolerated, not because it is effective.

EXPLORE ENFOS TODAY

The Strategic Consequences

Segmented ownership of Environmental Obligations creates persistent governance and control failures.

Control and Governance Failure: When ownership is fragmented, no single function can assert control over the full Environmental Obligation lifecycle. Period activity cannot be fully traced, tested, or defended across functions. Decisions are made with partial visibility. Changes go unaddressed because responsibility is diffused. When issues surface, accountability is unclear because no one owns the whole.

Financial Statement and Audit Risk: Fragmented ownership produces inconsistent assumptions and incomplete documentation. Environmental Obligation balances may be misstated when accounting and operational views diverge. Audit responses require reconstruction across multiple systems and stakeholders rather than controlled retrieval from a governed source of record. Audit effort increases while confidence in the number’s declines.

Loss of Executive and Board Visibility: Executives and boards cannot exercise effective oversight when answers to basic questions depend on which function is asked. Environmental Obligation exposure, reserve adequacy, and obligation status vary by source. Strategic decisions, including transactions and portfolio actions, proceed on incomplete or conflicting information. The board sees reported numbers without visibility into the governance gaps underneath. That is not oversight. It is exposure.

Segmented ownership conceals risk during steady-state operations. It is exposed under scrutiny, when governance gaps are hardest to correct and the cost of misalignment is highest.

Category Implication

Environmental Obligations cannot be governed through fragmented ownership and disconnected systems.

Environmental Obligation Management requires centralized governance across accounting, operations, legal, and external stakeholders, anchored in a single governed system of record. That system must preserve ownership, accountability, and traceability across the full Environmental Obligation lifecycle while enabling cross-functional participation without losing control.

Without unified governance, inventory completeness cannot be sustained, measurement cannot be defended, and execution cannot be reconciled. Environmental Obligation Management exists to restore control where segmented ownership has eroded it.

.webp)